By JASON BIRCH and JACQUELINE HARGREAVES

The practice of prostrating oneself on the ground, usually to a deity or guru, is mentioned in Sanskrit works, including some Tantras, that date back to at least the early medieval period of India’s history (i.e., 6th c. CE onwards). There were different ways of performing a prostration, some requiring that eight limbs be placed on the ground (aṣṭāṅgapraṇāma) and others stipulating that only six, five or four limbs touch the ground. Apart from paying homage to a deity or guru by bowing the head and holding the hands in the prayer gesture (añjalimudrā), medieval yoga texts do not mention prostrations such as the Aṣṭāṅgapraṇāma, nor any other type of Namaskāra, as a yoga technique.

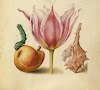

However, we have recently found an exception: An undated Jain Yogāsana manual, which may have been written in the nineteenth-century, describes a five-limbed prostration (namaskāra) as an āsana. The five limbs, which are brought together on the ground, are the two knees, two hands and forehead.

|

| Detail of Pañcāṅganamaskārāsana Yogāsanam (circa 19th century) |

The Āsana of Prostration with Five Limbs - Pañcāṅganamaskārāsana

Having brought together the knees, hands and forehead on the ground, the excellent [yogin] should venerate with the [proper] sentiment a god that should be worshipped [thus] with five [limbs]. Purification of the mind and an increase of merit arise by [prostrating] with these limbs. The 'Āsana of Prostration with Five Limbs' posture has been taught by the gods.

pañcāṅganamaskārāsanam ||15||

jānukaralalāṭān sa ekīkṛtya bhuvastale |

vandeta bhāvato bhavyaḥ prabhuṃ pūjyaṃ ca pañcakaiḥ ||29||

bhāvaśuddhiḥ puṇyavṛddhir aṅgair ebhiś ca jāyate |

pañcāṅganamaskāraṃ tu pīṭhaṃ devaiḥ samīritam ||30||

29a sa ] conj. : ya codex.

This unpublished Jaina manuscript contains descriptions of 108 āsanas with illustrations of each and provides an interesting window into the practice of late-medieval āsanas.1 It has been discussed in an article published in Kaivalyadhama’s Yoga Mīmāṃsā Journal.

In his commentary on the fifteenth-century Haṭhapradīpikā, Brahmānanda (19th century) advised against practising many repetitions of Sūryanamaskāra and weightlifting because, in his opinion, such practices were too strenuous.2 His comments were prompted by the Haṭhapradīpikā’s caveat against afflicting the body (kāyakleśa).

It is difficult to know whether Brahmānanda gave this advice because he disapproved of some yogins who were combining many repetitions of Sūryanamaskāra with Haṭhayoga. It may simply be that he considered Sūryanamaskāra and weightlifting to be good examples of practices that can afflict the body if done excessively. Nonetheless, one must wonder what Brahmānanda would have thought of the many strenuous āsanas described in late-medieval texts such as the Haṭharatnavalī, the Jogapradīpyakā and the Haṭhābhyāsapaddhati, the last of which contains moving and repetitive āsanas designed, as the text states, to develop bodily strength.3

As Mark Singleton has argued, a fairly strenuous form of Sūryanamaskāra, which extends the practice of prostrating oneself on the ground by adding dog poses and lunges, was combined with yoga in the twentieth century as part of an Indian nationalist attempt to promote physical culture.4 As far as we are aware, there is no evidence for a medieval Sūryanamaskāra that resembles the modern one.

We would like to thank James Mallinson for his comments on a draft of this post and to thank Seth Powell for providing a copy of the folio image.

(1) Satapathy B, Sahay GS., A brief introduction of "Yogāsana - Jaina": An unpublished yoga manuscript

Yoga Mimamsa [serial online] 2014 [cited 2016 Jun 19];46:43-55.

(2) Birch Jason, The Yogataravali and the Hidden History of Yoga

Namarupa Magazine, Spring, 2015, pp. 11-12

(3) Birch Jason, The Proliferation of Asana in Late Mediaeval Yoga Traditions

Yoga in Transformation: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on a Global Phenomenon

Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht Unipress (forthcoming 2016)

(4) Singleton Mark, Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice

Oxford University Press (2010)

Related posts: