|

| Yogī with chakras depicted on the body. Early 19th-century painting. Add MS 24099, f. 118. British Library. |

What follows is an extract from my forthcoming book, The Truth of Yoga. Subtitled “A comprehensive guide to yoga’s history, texts, philosophy, and practices,” it draws on the abundance of recent research to bring scholarly knowledge to general readers. My aim is to keep things clear—and as accessible as possible—without oversimplifying.

Inevitably, this is a difficult balance to strike, but I think one worth seeking. As I explain in the book, I decided to write it because students often ask me to recommend an overview of history and philosophy. While there are many fine works on more specialist subjects, these are easier to read with a grasp of the basics. However, many titles that are aimed at practitioners are misleading. Yogic texts are often reinterpreted to sound more appealing, or to make tenuous links to contemporary practice.

The example below is a case in point. It explores the evolution of teachings on chakras (I have chosen not to use diacritics, instead modifying the spellings of Sanskrit terms to reach the widest possible audience).1 Many yoga teacher trainings present them in ways that are barely related to traditional sources. Chakras have become a general shorthand for subtle anatomy, whose mystical mechanisms transcend distinctions between mind and body.

One of the biggest contributions of Tantra to physical yoga is a means to awaken this inner dimension and tap its potential for transformation. An overly materialist view can obscure how it works. Regardless of whether chakras exist in a dissected corpse, they are brought into being through visualization. As a result, they have powerful effects, but this is not quite the same as the logic of workshops that teach how to “cleanse” them.

|

| Durgā in a chakra with Gaṇeśa and lion. Ink and watercolour on paper, Pahari, probably Guler, second half 18th century. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. |

IMAGINARY CHAKRAS

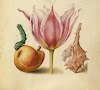

The best-known parts of the yogic body are often the most misunderstood. Chakras are subtle “wheels” along the spine, originally used as concentration points. They only really exist if imagined into being. Some teachings on yoga neglect them completely.There are many different systems of chakras, with varying numbers and locations. The predominant model today, with six along the spine and a seventh at the crown, is a mix of tradition and recent invention. The earliest reference comes from the tenth-century Kubjikamata Tantra (11.34–35), describing the anus as the adhara, a “base” or “support,” to which mula, or “root,” is later added as a prefix. The svadhishthana is located above it at the penis, manipuraka (or manipura) at the navel, and anahata in the heart. Vishuddhi is in the throat, and ajna between the eyes.

Generally, chakras are meant to be templates for visualization. They are presented in Tantras as ways to transform a practitioner’s body, installing symbols connected to gods. Some texts list more than a dozen, others fewer than five. They are sometimes called adharas, or “supports” for meditation—or alternatively padmas, or “lotuses,” on account of the petals that frame their designs. Either way, they are said to be hubs in a network of channels for vital energy, and focusing on their positions refines perception.

Another early list gives different names: nadi, maya, yogi, bhedana, dipti, and shanta. “Now I will tell you about the excellent, supreme, subtle visualizing meditation,” says the Netra Tantra (7.1–2),2 describing the body as comprising “six chakras, the supporting vowels, the three objects, and the five voids, the twelve knots, the three powers, the path of the three abodes, and the three channels.” This bewildering array of locations is common in Tantras, whose maps of inner realms often sound contradictory.

A few centuries later, the seven-chakra version became more established. This adds the sahasrara—a “thousand-spoked” wheel, or “thousand-petaled” lotus—at the top of the head (or sometimes above it, as in the Shiva Samhita). Another yogic text lists the same seven points without mentioning chakras: “The penis, the anus, the navel, the heart and above that the place of the uvula, the space between the brows and the aperture into space: these are said to be the locations of the yogi’s meditation” (Viveka Martanda 154–55).3 However the points are defined, they function as markers for raising awareness.

New Age authors have blurred the distinction between mental creations and physical fact, presenting chakras as if they exist, as opposed to being visualized. They are often depicted with rainbow colors not found in original Sanskrit sources. They are also given attributes that link them to gemstones, planets, ailments, endocrine glands, suits of the Tarot, and Christian archangels, among other details.

Some mentions of mantras are also misleading. Tantric rituals connect them to elements pictured in chakras, not the chakras themselves. So reciting a “seed”—or bija—mantra linked to air is unlikely to do much to open the heart, except via placebo effects. However, focusing attention on such things can make them real, at least in the realm of subjective experience. And since this is how Tantras say deities are summoned, perhaps the use of chakras by modern practitioners is not all that different.