A 19th-century Brajbhāṣā Reworking of the Kokośātra

Download this article as a PDF

A reference by Gudrun Bühnemann (2007: 158) to eighty-four āsanas in Kāmaśāstra (‘treatises on sexual pleasures’) prompted me to search the well-known works of this genre, such as the Kāmasūtra, for complex postures that might be the same as those in yoga texts. Seeing that several āsanas in the Mallapurāṇa, a Sanskrit work on wrestling, have the same names as those found in yoga texts,1 it is not inconceivable that similarities, borrowings and ‘cross-pollination’ occurred between Kāmaśāstra and yoga.

Bühnemann mentions a list of eighty-four āsanas in the Kokaśāstra (‘Koka’s treatise’) based on a citation in a recent Marathi book called the Saṅkhyāsaṅketakośa by Haṇmante (1980). The Kokaśāstra, also known as the Ratirahasya (‘secrets of passion’), is a Sanskrit work usually dated to the twelfth century, which is approximately the same period when the earliest texts of Haṭha- and Rājayoga were composed. The authors of two early yoga texts, namely the Dattātreyayogaśāstra and the Vivekamārtaṇḍa, explicitly state that they are aware of the existence of numerous āsanas, of which Śiva taught eighty-four. However, both authors chose to teach only one or two for the purpose of Haṭhayoga (Birch 2018: 107-108).

Sexual positions are described in the tenth chapter of the Sanskrit Kokaśāstra. Contrary to Haṇmante’s claim, the Kokaśāstra does not mention eighty-four āsanas, but rather describes forty-two karaṇas (‘positions’) and notes the names of a few others. The positions are divided into five types: supine (uttāna), on the side (tiryak), sitting (āsitaka), standing (sthita) and bent over (ānata).

The author seems to prefer the term karaṇa, rather than āsana, to refer to a sexual position.2 In contexts of yoga, karaṇa can be used as a synonym for the mudrās of Haṭhayoga, such as viparītakaraṇī. However, there are a few instances where it means āsana. A clear example is found in a Jain yoga text called the Yogapradīpa, which incorporates a system of aṣṭāngayoga with an auxiliary called karaṇa. In a subsequent verse (135), it glosses karaṇa as āsana.3

It is worth noting that the author of the Kokaśāstra uses the word āsana in regard to only one posture, which is padmāsana. The position is described as 'crossing the shanks' and is prescribed for a young woman (yuvati). A 'half-legged' variation (ardhapadmāsana) is also described in the same verse.4 Padmāsana is mentioned in the Kāmasūtra (2.6.32) as well, so its inclusion as a sexual position in the Kokaśāstra is no surprise. However, in both works padmāsana is the only instance where the word āsana is used in the sense of seated posture, and this is probably more an indication of the renown of padmāsana throughout the ages, rather than an association of the term āsana with sexual positions.

In a previous publication (2018: 108 n. 19), I speculated that Haṇmante might have been citing a more recent version of the Kokaśāstra. According to various manuscript catalogues, the Sanskrit work appears to have inspired several related texts in vernacular languages, like the Kokamañjarī and the Ratimañjarī, to which I did not have access at the time.

I have recently consulted a manuscript of a Brajbhāṣā reworking of the Kokaśāstra, which has a reference to eighty-four āsanas. According to its colophons, the text is called the Koka. It has a scribal date of 1850 CE.5 The codex consists of handwritten Devanagari script, various tables with rulered lines and forty-one elegant line drawings in blank ink of couples. Each illustration has ornate borders and simple backgrounds of lamps, cushions, beds and flooring. A comment on the thirty-fourth folio appears to summarise the three parts of the text as follows:

The unique bound manuscript featured in this article is an abridged rendering of the Kokaśāstra. Its content may have been taken from a longer version which contained more information on a complete collection of eighty-four āsanas.

As far as I am aware, eighty-four positions are not described or mentioned by Vātsyāyana, the author of the Kāmasūtra. In fact, he was more partial to the number sixty four, as he refers several times to the sixty-four arts (kalā) or methods (yoga) of lovemaking.6 Nonetheless, references to the eighty-four positions of Kāmaśāstra are not uncommon in modern publications. In an interview, for example, Osho (2004: 127) was reported as saying:

I am yet to find a premodern work in the literature of Kāmaśāstra with such a collection of positions and it may be just a matter of time (and funding) before one comes to light. Although some of the positions may have similar forms, based on what I have read in the Kāmasūtra and the Kokaśāstra, I doubt whether yogis were inspired by the amorous positional play of specialists in erotica or vice-versa.

1 See Mallapurāṇa 8.16cd – 21ab. This work lists the names of seventeen āsanas, including siṃhāsana, kūrmāsana, gajāsana and bhujāsana, which are found in yoga texts composed between the 16-18th century. The Mallapurāṇa does not describe these āsanas, so it is not possible to know whether the author was referring to postures with similar shapes as those of the same names in yoga texts.

2 The term karaṇa is used in Kokaśāstra 10.14, 10.17 and 10.18.

3 Yogapradīpa 50-51ab (saṃyamo niyamaś caiva karaṇaṃ ca tṛtīyakam | prāṇāyāmapratyāhārau samādhir dhāraṇā tathā ||50|| dhyānaṃ cetīha yogasya jñeyam aṣṭāṅgakaṃ budhaiḥ | … | niyamaḥ pañcadhā jñeyaḥ karaṇaṃ punar āsanaṃ). In the Mataṅgapārameśvaratantra (Yogapāda 2.23cd-28), karaṇa refers more specifically to the position of the hands, eyes, tongue, jaw, neck, etc., in a seated posture. The postural details are said to be taught for sole purpose of yoga (yogamātrokta). For this reading, see Creismeas (2015: 28).

4 Kokaśāstra 10.25 (jaṅghāyugalasya viparyayataḥ padmāsanam uktam idaṃ yuvateḥ | jaṅghaikaviparyayatas tu bhaved idam eva tadardhapadmapadam || 25d -padmapadam ] emend. : -padopapadam (to restore the metre).

5 Koka f. 70: san 1850 ī◦. I am unsure of the word or phrase for which the ī◦ stands. The author’s or scribe’s name may be Matavaparāvalapiṇḍī.

6 For examples, see 1.3.13, 2.2.1-3, etc.

Bühnemann mentions a list of eighty-four āsanas in the Kokaśāstra (‘Koka’s treatise’) based on a citation in a recent Marathi book called the Saṅkhyāsaṅketakośa by Haṇmante (1980). The Kokaśāstra, also known as the Ratirahasya (‘secrets of passion’), is a Sanskrit work usually dated to the twelfth century, which is approximately the same period when the earliest texts of Haṭha- and Rājayoga were composed. The authors of two early yoga texts, namely the Dattātreyayogaśāstra and the Vivekamārtaṇḍa, explicitly state that they are aware of the existence of numerous āsanas, of which Śiva taught eighty-four. However, both authors chose to teach only one or two for the purpose of Haṭhayoga (Birch 2018: 107-108).

|

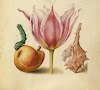

| Figure 1: The Koka, folio 45. |

Sexual positions are described in the tenth chapter of the Sanskrit Kokaśāstra. Contrary to Haṇmante’s claim, the Kokaśāstra does not mention eighty-four āsanas, but rather describes forty-two karaṇas (‘positions’) and notes the names of a few others. The positions are divided into five types: supine (uttāna), on the side (tiryak), sitting (āsitaka), standing (sthita) and bent over (ānata).

The author seems to prefer the term karaṇa, rather than āsana, to refer to a sexual position.2 In contexts of yoga, karaṇa can be used as a synonym for the mudrās of Haṭhayoga, such as viparītakaraṇī. However, there are a few instances where it means āsana. A clear example is found in a Jain yoga text called the Yogapradīpa, which incorporates a system of aṣṭāngayoga with an auxiliary called karaṇa. In a subsequent verse (135), it glosses karaṇa as āsana.3

It is worth noting that the author of the Kokaśāstra uses the word āsana in regard to only one posture, which is padmāsana. The position is described as 'crossing the shanks' and is prescribed for a young woman (yuvati). A 'half-legged' variation (ardhapadmāsana) is also described in the same verse.4 Padmāsana is mentioned in the Kāmasūtra (2.6.32) as well, so its inclusion as a sexual position in the Kokaśāstra is no surprise. However, in both works padmāsana is the only instance where the word āsana is used in the sense of seated posture, and this is probably more an indication of the renown of padmāsana throughout the ages, rather than an association of the term āsana with sexual positions.

|

| Figure 2 (top): The Koka, folio 46. Figure 3 (bottom): The Koka, folio 52. |

In a previous publication (2018: 108 n. 19), I speculated that Haṇmante might have been citing a more recent version of the Kokaśāstra. According to various manuscript catalogues, the Sanskrit work appears to have inspired several related texts in vernacular languages, like the Kokamañjarī and the Ratimañjarī, to which I did not have access at the time.

I have recently consulted a manuscript of a Brajbhāṣā reworking of the Kokaśāstra, which has a reference to eighty-four āsanas. According to its colophons, the text is called the Koka. It has a scribal date of 1850 CE.5 The codex consists of handwritten Devanagari script, various tables with rulered lines and forty-one elegant line drawings in blank ink of couples. Each illustration has ornate borders and simple backgrounds of lamps, cushions, beds and flooring. A comment on the thirty-fourth folio appears to summarise the three parts of the text as follows:

- The different types of women and men (strī aura puruṣa ke bheda haiṃ).

- Eighty-four āsanas (caurāsī āsana haiṃ).

- Mantras and herbs (mantra aura auṣadhi hai).

|

| Figure 4 (top): The Koka, folio 38. Figure 5 (bottom): The Koka, folio 59. |

The unique bound manuscript featured in this article is an abridged rendering of the Kokaśāstra. Its content may have been taken from a longer version which contained more information on a complete collection of eighty-four āsanas.

As far as I am aware, eighty-four positions are not described or mentioned by Vātsyāyana, the author of the Kāmasūtra. In fact, he was more partial to the number sixty four, as he refers several times to the sixty-four arts (kalā) or methods (yoga) of lovemaking.6 Nonetheless, references to the eighty-four positions of Kāmaśāstra are not uncommon in modern publications. In an interview, for example, Osho (2004: 127) was reported as saying:

A book of tremendous importance, by Vatsyayana, has been in existence for 5,000 years. The name of the book is Kama Sutra, hints for making love. And it comes from a man of deep meditation – he has created eighty-four postures […]

I am yet to find a premodern work in the literature of Kāmaśāstra with such a collection of positions and it may be just a matter of time (and funding) before one comes to light. Although some of the positions may have similar forms, based on what I have read in the Kāmasūtra and the Kokaśāstra, I doubt whether yogis were inspired by the amorous positional play of specialists in erotica or vice-versa.

Notes

2 The term karaṇa is used in Kokaśāstra 10.14, 10.17 and 10.18.

3 Yogapradīpa 50-51ab (saṃyamo niyamaś caiva karaṇaṃ ca tṛtīyakam | prāṇāyāmapratyāhārau samādhir dhāraṇā tathā ||50|| dhyānaṃ cetīha yogasya jñeyam aṣṭāṅgakaṃ budhaiḥ | … | niyamaḥ pañcadhā jñeyaḥ karaṇaṃ punar āsanaṃ). In the Mataṅgapārameśvaratantra (Yogapāda 2.23cd-28), karaṇa refers more specifically to the position of the hands, eyes, tongue, jaw, neck, etc., in a seated posture. The postural details are said to be taught for sole purpose of yoga (yogamātrokta). For this reading, see Creismeas (2015: 28).

4 Kokaśāstra 10.25 (jaṅghāyugalasya viparyayataḥ padmāsanam uktam idaṃ yuvateḥ | jaṅghaikaviparyayatas tu bhaved idam eva tadardhapadmapadam || 25d -padmapadam ] emend. : -padopapadam (to restore the metre).

5 Koka f. 70: san 1850 ī◦. I am unsure of the word or phrase for which the ī◦ stands. The author’s or scribe’s name may be Matavaparāvalapiṇḍī.

6 For examples, see 1.3.13, 2.2.1-3, etc.

Bibliography

Sanskrit

KāmasūtraŚrīvātsyāyanapraṇītaṃ Kāmasūtram: Yaśodhara-viracitayā Jayamaṅgalākhyayā ṭīkayā sametam. Vātsyāyana. Ed. Dvivedī, D. Mumbaī [Bombay]: Nirṇaya Sāgara Pr., 1900.

Mallapurāṇa

Mallapurāṇa: A Rare Sanskrit Text on Indian Wrestling especially as practised by the Jyeṣṭimallas. Ed. Bhogilal Jayachandbhai Sandesara and Ramanlal Nagarji Mehta. Baroda: Oriental Institute, 1964.

Yogapradīpa

For details, see Birch, J. & Hargreaves, J. 2017. The Yogapradīpa: A Premodern Jain ‘Light on Yoga’. The Luminescent. Retrieved from: https://www.theluminescent.org/2017/03/the-yogapradipa-premodern-jain-light-on.html. Accessed on: 16 May 2019.

Brajbhāṣā

KokaKoka: Strī aura puruṣa ke bheda, caurāsī āsana, mantra aura auṣadhi. Tübingen: Universitätsbibliothek, 1850. Retrieved from: http://soas.worldcat.org/oclc/1083973120.

English

Birch, Jason. 2018 (submitted 2013). "The Proliferation of Āsana-s in Late-Mediaeval Yoga Texts." In Yoga in Transformation: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, edited by K. Baier, Philipp A. Maas, Karin Preisendanz, p. 101-180. Göttingen: V&R Unipress. Retrieved from: https://doi.org/10.14220/9783737008624.Bühnemann, Gudrun. 2007. Eighty-Four Āsanas in Yoga: A Survey of Traditions (with Illustrations). New Delhi: D.K. Printworld.

Osho. 2004. The Book of Man. New Dehli: Penguin Books.

French

Creismeas, Jean-Michel. 2015. Le yoga du Mataṅgapārameśvaratantra à la lumière du commentaire de Bhaṭṭa Rāmakaṇṭha. Religions. Université Sorbonne Paris Cité.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright with the Author. This publication is made available as share alike, in full, with attribution to the author and publisher.

Copyright with the Author. This publication is made available as share alike, in full, with attribution to the author and publisher.

CITATION:

Birch, Jason. 2019. “Eighty-four Āsanas for Sexual Pleasure: A 19th-century Brajbhāṣā reworking of the Kokaśāstra.” The Luminescent, 17 May, 2019. Retrieved from: www.theluminescent.org.

• ONE OFF DONATION •

FRIEND . PATRON . LOVER

♥ $1 / month

♥ $5 / month

♥ $10 / month

♥ $25 / month

♥ $50 / month

Related Posts

Headstand on the Fingers: Yogis on their Heads in the Early Modern Period

Āsanas Old and New: Unpublished manuscripts and hints of the missing Yoga Kurunta