by JACQUELINE HARGREAVES

Download this article as a PDF

Ever since the Sun has cast a shadow on the land that is now India, it seems that people have offered their reverence in worship of its brilliance, sustenance and cyclical presence. Terracotta plates and medallions from the Mauryan dynasty1 (circa 321–185 B.C.) provide the earliest anthropomorphic representations of Sūrya, the Sun god. Sculptural representations appear on a railing of the Bodhgayā Stupa.2 There is abundant inscriptional as well as textual evidence to testify to the prevalence of Sun worship from the Gupta period onward. Several architectural temples in honour of a Sun god still exist, although often in ruins, such as the majestic 13th century Sun Temple of Koṇārka that sits in the jungle on the coastline of Orissa.

Download this article as a PDF

|

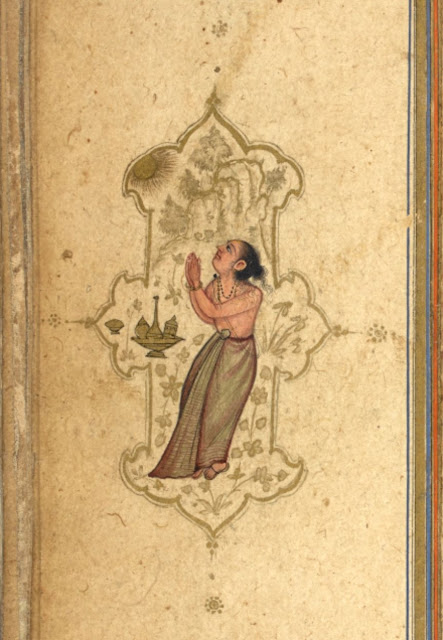

| Fig. 1: Folio 36r from the Dīvān of Ḥāfiẓ, (Collected poems of Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad Ḥāfiẓ Shīrāzī). British Library, Manuscript Or 14139. |

Ever since the Sun has cast a shadow on the land that is now India, it seems that people have offered their reverence in worship of its brilliance, sustenance and cyclical presence. Terracotta plates and medallions from the Mauryan dynasty1 (circa 321–185 B.C.) provide the earliest anthropomorphic representations of Sūrya, the Sun god. Sculptural representations appear on a railing of the Bodhgayā Stupa.2 There is abundant inscriptional as well as textual evidence to testify to the prevalence of Sun worship from the Gupta period onward. Several architectural temples in honour of a Sun god still exist, although often in ruins, such as the majestic 13th century Sun Temple of Koṇārka that sits in the jungle on the coastline of Orissa.

During the time of the Mughal court, we find evidence of a reasonably liberal religious policy3 where the 16th-century Mughal Emperor Akbar the Great (1556 - 1605) adopted a sunrise practice of presenting himself at the jharokha-i-darshan,4 an ornate balcony window from which his subjects were able to view him at first light after bathing in the river and performing their own Sun observance practices.

Apart from the representation of the Sun as a deity and object of worship, very little iconographic evidence of the devotees themselves has survived the passing of time. However, one such piece of evidence appears in paintings from the Mughal court. In the decorative marginal borders of an illustrated manuscript of the Dīvān of Ḥāfiẓ, ‘The Collected poems of Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad Ḥāfiẓ Shīrāzī',5 two naturalistic images depict Sun worshipers.

According to a note in this manuscript,6 these poems have been scribed by the renowned calligrapher Sulṭān ʻAlī Mashhadī in circa 1470 AD. The whole work was refurbished during the reign of the 4th Mughal Emperor Jahāngīr7 (son of Akbar) and thus provide an accurate date for the outer margins at circa 1605 AD. These illuminated borders (fig. 1) contain elaborate cartouches with precise depictions of flora, fauna, landscapes, Persian musicians, hunters, fakirs, a Nath yogi and even Europeans.

|

| Fig. 2: Detail of a Sun worshiper from folio 36r of the Dīvān of Ḥāfiẓ, (Collected poems of Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad Ḥāfiẓ Shīrāzī). British Library, Manuscript Or 14139. |

The first of the Sun worship scenes is in a small golden cartouche centred on the right-hand border of folio 36r (fig. 2). It features a male figure standing in a garden with floral and cloud-like decorations around him. He is wearing a simple dhoti and a cloth (aṅgavastra) wrapped over his shoulders. His hands are raised above his head clasping mālā beads and his gaze is upwards towards the Sun, which is shining brightly overhead. The man’s shoulder-length hair is sleekly combed, as if oiled, and although he appears to be a Brahmin, it is somewhat uncertain because his sacred thread (yajnopavita) is not visible and no other sectarian marks are displayed. The prominent feature of mālā beads suggest that he could be performing japa (i.e., mantra recitation) to the Sun, which is a Brahmanical practice described in the Veda. His dhoti is tied in the style that is typical of South India, and this is affirmed by the accompanying aṅgavastram. The remainder of the margin for this folio pictures birds and plants in similarly elaborate gold painted frames.

|

| Fig. 3: Detail of a Sun worshiper from folio 45r of the Dīvān of Ḥāfiẓ, (Collected poems of Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad Ḥāfiẓ Shīrāzī). British Library, Manuscript Or 14139. |

The second scene of Sun worship is centred on the right-hand border of folio 45r (fig. 3) and is similarly positioned in a golden cartouche. It features a youthful male figure standing with his hands in a gesture of reverence (generally called añjalimudrā) towards the Sun. The scared thread (yajñopavītam) over his bare right shoulder is clearly visible in the fine details of the figure, marking him as a Brahmin. His hair is long and worn in a bun at the crown of the head, and he has bracelets on both wrists as well as beaded necklaces around his neck. His dhoti is worn at full length and gathered at the front. The brass accoutrements, that are typically used for pūjā, sit to his left. A mountainous landscape is detailed faintly in the background. The remainder of the outer margin for this folio contains similarly framed gold-painted cartouches with fine drawings of birds, a rabbit and a deer-like animal.

These two Sun worship scenes are remarkable because not only do they focus on Sun worshippers, rather than the Sun as a deity or image accompanied by consorts and devotees, but they are, as far as I am aware, the earliest naturalistic painted evidence of Sun worshipers themselves.

One other painting of significance can be found in the Gulshan Album8 (circa 1590-95) from the Mughal artist studio of Lahore or Delhi (fig. 4). Attributed to Basawan and dated to a similar period as the outer borders of the Dīvān of Ḥāfiẓ, it depicts a woman worshiping the Sun with a child at her feet. Both figures in the painting are rendered with three dimensional perspective forming a realistic outdoor scene. Draped fabric in vibrant blue and red is given weight and movement through the use of shading. The distant landscape is seen through an atmospheric haze. The figures and landscape are an example of the fully developed naturalistic style of the Mughal studio. Based on the woman’s head dress, costume and golden hair, it is likely that this painting is representing an imagined European rather than a Hindu or Brahmin sun worshiper. This painting demonstrates the significant influence European art was having on Mughal artists of the time.9 The representation of mother and child harps to Christian imagery that entered the Mughal artistic milieu during the second half of the 16th century through European prints and illustrated Bibles gifted by Jesuit missionaries and other European travellers to Emperor Akbar’s court.

NOTES

1 Dasgupta, P. C., Early Terracotta from Chandraketugarh, Lalit Kala No.6. Oct. 1959. p. 46. Vide also Indian Archaeological Review, 1955-56. Pl. LXXII B., also Modern Review, April, 1956. The terracotta image of Sun-god from Chandraketugarh. This terracotta was collected by S. Ghosh, and is now preserved in Asutosh Museum, Calcutta (T. 6838). Also see Bindheswari P. Singh, Bharatiya Kala Ko Bihar Ki Den, (Hindi) JISOA, Vol. III, No. 2. 1935. P. 82, 125; Photo No. 46.

2 Pandey, Lalta Prasad, Sun Worship in Ancient India. Shantilal Jain at Shri Jainendra Press, Delhi. First Edition 1971. Plate 5, Figure 1 Bodhagayā sun image.

3 Proceedings – Indian History Congress. Indian History Congress (1998), p. 246.

4 Eraly, Abraham, The Mughal World: Life in India's Last Golden Age. Penguin Books India (2007), p. 44.

5 Dīvān of Ḥāfiẓ (Collected poems of Shams al-Dīn Muḥammad Ḥāfiẓ Shīrāzī). British Library, Manuscript Or 14139. Accessed: http://www.bl.uk/manuscripts/Viewer.aspx?ref=Or_14139_fs001r.

6 The catalogue record at the British Library provides the note by Shah Jahan of 1037/1628 (f.1r) that identifies the calligrapher as Sulṭān ʻAlī Mashhadī and that the manuscript was copied at Herat or Mashhad ca. 1470. It appears that the source of this catalogue record is J. P. Losty, The 'Bute Hafiz' and the Development of Border Decoration in the Manuscript Studio of the Mughals, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 127, No. 993 (Dec., 1985), p. 856. Losty gives a clear account of his study of the marginal notes on the manuscript that have enable him to precisely date the outer borders to 1014/1605. This includes an accidentally studio mark that has remained on the margin as well as a minute inscription on a scroll bearing a date of 1014/1605 in the hands of a Portuguese gentleman painted on f.18r.

7 Fourth Mughal Emperor Jahāngīr was born on 31 August 1559 and died on 28 October 1627. Jahāngīr - Emperor of India, Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica. Published 1998 and revised 2015. Accessed: https://global.britannica.com/biography/Jahangir.

8 Muraqqa-i Gulshan (Gulshan Album) is dated 1599-1609 and is mostly in the former Gulistan Palace Library, Tehran. The painting of concern for this article: Woman Worshiping the Sun: Page from the Gulshan Album, has been lent by Museum of Islamic Art, Doha to The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

9 Losty, J.P., The 'Bute Hafiz' and the Development of Border Decoration in the Manuscript Studio of the Mughals, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 127, No. 993 (Dec., 1985), pp. 855-856+858-871.

Download this article as a PDF

9 Losty, J.P., The 'Bute Hafiz' and the Development of Border Decoration in the Manuscript Studio of the Mughals, The Burlington Magazine, Vol. 127, No. 993 (Dec., 1985), pp. 855-856+858-871.

Download this article as a PDF