SOAS Centre of Yoga Studies – Chair Notes

|

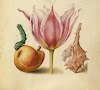

| Figure 1: Cāmuṇḍā. Khajuraho region (10-11th century). Harvard Art Museums/Arthur M. Sackler Museum. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Howard E. Houston. |

For five weeks in the Summer Term 2019 the SOAS Centre of Yoga Studies organised a study group on yoga and gender. The seminars were an opportunity for students and researchers to engage with cutting edge work being conducted through SOAS and further afield and show-case rising researchers as well as more established scholars. We wanted to explore yoga and gender from a cross-disciplinary approach, integrating philology, ethnography, sociology, iconography and critical theories—exploring themes of gender, sex, power and abuse, female praxis, the esoteric feminine and ferocious goddesses in historical and contemporary contexts.

As a research student at SOAS working on constructions of gender in Sanskrit texts on Haṭhayoga convening this group was an opportunity to learn from colleagues and extend research networks. Alongside the fascinating content, I was keen to see how different projects were designed and carried out practically, and how contrasting methodologies and theories were drawn upon to interrogate the data.

The format for the sessions was short presentations followed by interactive discussions based on both the material presented and prior set readings. The intention was to curate an environment where interaction of ideas and reflection was optimised. The sessions were well attended by an inquisitive and diverse body of academic researchers and yoga professionals including teachers, museum guides, and documentary film-makers and photographers.

SOAS welcomed five researchers: Monika Hirmer, a SOAS doctoral researcher working on goddess worship at a Kāmākhyā shrine; Daniela Bevilacqua, a post-doctoral ethnographer working on the Hatha Yoga Project; Amelia Wood, a SOAS doctoral researcher working on abuse of power in modern yoga; Suzanne Newcombe, Open University Lecturer and AyurYog post-doctoral researcher who has published on women in Britain; and Sandra Sattler, a philologist and art historian at SOAS researching for a doctoral degree on fierce goddesses. We were also able to include a presentation by Agi Wittich, a doctoral researcher at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem working on women in the Iyengar yoga tradition.

Kāmākhyā Worship

Ritualised, tactile, erotic devotion was a feature of the Kāmākhyā worship explored by Monika Hirmer who is working on ‘Becoming the Goddess: Study of a contemporary South Indian Tantric tradition and its implications for concepts of personhood, gender relations and everyday life.’ Monika’s presentation explored the outcomes of her research in relation to worshipping and embodying the goddess, entitled ‘Playing (with) Devī: Praxis, māyā and ungendered femininity’. Monika introduced the methodology of her fieldwork, provided an ethnographic profile of the temple complex where she worked and described the cosmology that informs the life of the Śrīvidyā practitioners she lived with. Monika analysed Devī’s propensity for play (līlā), the shrine which plastically expresses Devī’s yoni and womb, and a conception of the body at atomic and subtle level. Monika argues that this points to a pervasive underlying feminine substratum.

Some of the social implications of this practice are a valorising of maternal qualities in male as well as female devotees. Monika described caste inversions, yet not as described by anthropological ritual theorists—the privileged status of the low-caste temple priestess extended beyond the duration of the ritual inversion—i.e., beyond the ritual itself.

This practice community appears to be living out the tantalising prospect of a feminine divine, beyond a polarity of masculine and feminine. Yet the feminine was still characterised with ideas of maternal sentiment. For Monika the absolute principle was specifically female: not beyond gender, but female. Monika described bindu as premanifest energy and the female absolute as the primordial creatrix. A fascinating discussion ensued around whether this female absolute could exist as gendered female prior to a masculinity in relationship with which such characteristics could be articulated: is it possible to have a female without a male referent?

Monika’s rationale behind suggesting the quite distinct readings for the session was to illustrate the different results derived from different approaches: Madhu Khanna (2016) was working from the everyday life of practitioners whilst David Gordon White (1998) was extrapolating a textual response.

Female Asceticism in India

The second session welcomed Daniela Bevilacqua to present ‘An historical and ethnographic view of yoga physical practices and female asceticism in India’. Daniela is a postdoctoral researcher on the ERC-funded Hatha Yoga Project, a South-Asianist collecting, through fieldwork, historical evidence of yoga practice and ethnographic data among living ascetic practitioners of yoga. She conducted doctoral research on the Rāmānandī Sampradāya and was awarded a doctoral thesis from the University of Rome, Sapienza and from the University of Paris X Nanterre Ouest La Défense. Daniela has recently published her first monograph Modern Hindu Traditionalism in Contemporary India which examines the Rāmānandī order (sampradāya) and gives a portrait of the Jagadguru Rāmānandācārya Rāmnareśācārya.

In her session with us Daniela explored ‘traditional’ female asceticism in India and the difficulties faced by women who want to become ascetics. She then gave a detailed case study of Rām Priya Dās, a female yoga practitioner who belongs to the Rāmānandī Sampradāya, a Vaiṣṇava order. Rām Priya Dās is one of the few examples of a yogi rāj, someone who has learnt the practices from childhood. There are few women in this category most likely due to the challenges faced by women who wish to become ascetics.

Daniela’s research on notions of Haṭhayoga amongst practitioner communities in India shows the disjunction between textual and ethnographic studies: rather than calling on textual sources to justify and source authority for their teachings there is a tendency to disparage written sources. One of Daniela’s articles we read for the session explored these themes in relation to āsana (Bevilacqua, 2017a). Our second reading focused on female practitioners (Bevilacqua, 2017b).

In her session with us Daniela explored ‘traditional’ female asceticism in India and the difficulties faced by women who want to become ascetics. She then gave a detailed case study of Rām Priya Dās, a female yoga practitioner who belongs to the Rāmānandī Sampradāya, a Vaiṣṇava order. Rām Priya Dās is one of the few examples of a yogi rāj, someone who has learnt the practices from childhood. There are few women in this category most likely due to the challenges faced by women who wish to become ascetics.

Daniela’s research on notions of Haṭhayoga amongst practitioner communities in India shows the disjunction between textual and ethnographic studies: rather than calling on textual sources to justify and source authority for their teachings there is a tendency to disparage written sources. One of Daniela’s articles we read for the session explored these themes in relation to āsana (Bevilacqua, 2017a). Our second reading focused on female practitioners (Bevilacqua, 2017b).

|

| Figure 2: Photograph of a sannyāsinī (female ascetic). Oman, John Campbell (1905: 227). The Indian Mystics & Saints of India. |

In looking at ‘gender’ there is a risk of equating gender with women’s studies. Here women are the category marked by gender whereas the male is the neutral, a priori body. Women tend to be characterised by social roles, particularly motherhood, and are associated with maternal expectations. In her above mentioned article on women ascetics, Daniela notes ‘Generalized labels to define what is “typical female” and what is “typical male” risk of flattening the idea of female asceticism’ (Bevilacqua, 2017b: 72). In our discussion of motherhood and gender where women are marked by maternal duties or sentiment, it emerged that men, even when engaged in paternal duties, are not marked by paternity. In contrast, Monika’s research found that men were positively characterised by maternal qualities as a mark of being closer to Devī.

The enduring image of Daniela’s session was a photo of the sādhvī Rām Priya Dās censored by biro: in an inversion her clothing slips down, and her exposed thigh has been scribbled over. As the Hatha Yoga Project enters its final year and the team turn to writing up their findings I look forward to reading further outputs.

|

| Figure 3: Photograph of Rām Priya Dās censored by biro. |

Yoga, Power and Gender

Amelia Wood is at the forefront of bringing a critical perspective to abuses of power in yoga, a topic which has recently received sustained attention particularly since the exposures prompted by the #metoo movement. Amelia is researching for a doctoral thesis at SOAS on ‘Yoga, power and gender: an investigation into the abuse of power by modern gurus’. Amongst the case studies that she is exploring are Bikram Choudhry (inventor of Bikram Yoga), Kausthub Desikachar (lineage holder to his grandfather’s legacy, TKV Krishnamacharya) and the head of Satyananda Yoga in Australia in the 1970s and 80s, Swami Akhandananda. The intersectional questioning she is bringing to bear on these cases include asking about the extent to which the transnational dislocation of cultural categories such as yoga, gender and spiritual authority has contributed to the abuse of power within the global modern yoga context. She brings a normative thrust to her project by asking ‘How can discussions of abuse support victims rather than those already in positions of power?’ Amelia has an unrelenting commitment to refocusing the critical gaze from the actions of gurus to the predicament of victims / survivors. We prepared for the session by reading Amanda Lucia’s theorising of abuse (Lucia, 2018) where the emphasis is placed on the structural, systemic dynamic of charisma opening up space for abuse to occur. Lucia defines ‘haptic logics’ as the ‘disciplinary logics of physicality’ and follows a social constructivist theory of charisma. Lucia argues for haptic logics as a systemic approach rather than the psychological analysis usually served to ‘headline stealing hyper gurus’.

Lucia mingled emic and etic approaches by placing affect theory alongside a more Āyurvedic and energetic understanding of the porousness of bodies and ritual purity: ‘Through gaining proximity, devotees aim to consume the affective power of the guru—to absorb it into their bodies. The possibility of this transmission depends on the premise that bodies are comprised of porous boundaries that interact with and absorb from others and their environments. As Teresa Brennan has argued, affect, or “the physiological shift accompanying a judgment” is also transmitted between bodies and their environments.’ Lucia explains that ‘Affect can also be explained as transmittable “force,” “energy,” and “physiological shift,” which makes it particularly applicable here because its transmission closely resembles the language used to interpret the guru’s transmission of śakti’ (Lucia, 2018: 967 ff). In her reading of work to date on abuse of power in yoga Amelia is careful to unpick the attribution of responsibility and agency, highlighting where it has been and often continues to be attributed to the victim / survivor.

Our second reading for this session was Josna Pankhania’s whistleblowing work on the Bihar School and the findings of the Australian Royal Commission of Inquiry (Pankhania, 2017). Of particular note for me was the essentialist East-West dichotomy which at times appear in the analysis. For example, one concern around trans-cultural dislocation of the guru-śiṣya (teacher-student) relationship is that Western communities import the teachings but not the controls, such that guru models are imported into spheres where the traditional role of a guru is not understood. Pankhania does note that this rhetoric is problematic. The Australian broadcaster ABC suggested that yoga taught according to Western standards would result in a decrease in abuse by asking, ‘Is the claiming of yoga now by the West as a western practice going to save it from abuse?’ Pankhania noted that ‘This concept is not only problematic, but also symptomatic of the West’s continued angst about ‘the white man’s burden’, the supposed duty of the white race to engage in civilising missions to liberate the ‘savages’’ (Pankhania, 2017: 115). Pankhania links this issue with the much broader debates around identity politics and the postcolonial critique, by noting that, ‘As ‘the white man’s burden’ is unable to convincingly justify European colonialism, so too a crisis of ethics in any yoga organisation can surely not be adequately resolved through the process of cultural appropriation by the West. Concern with abusive gurus is certainly very much present in Indian society, too.’

Lucia mingled emic and etic approaches by placing affect theory alongside a more Āyurvedic and energetic understanding of the porousness of bodies and ritual purity: ‘Through gaining proximity, devotees aim to consume the affective power of the guru—to absorb it into their bodies. The possibility of this transmission depends on the premise that bodies are comprised of porous boundaries that interact with and absorb from others and their environments. As Teresa Brennan has argued, affect, or “the physiological shift accompanying a judgment” is also transmitted between bodies and their environments.’ Lucia explains that ‘Affect can also be explained as transmittable “force,” “energy,” and “physiological shift,” which makes it particularly applicable here because its transmission closely resembles the language used to interpret the guru’s transmission of śakti’ (Lucia, 2018: 967 ff). In her reading of work to date on abuse of power in yoga Amelia is careful to unpick the attribution of responsibility and agency, highlighting where it has been and often continues to be attributed to the victim / survivor.

Our second reading for this session was Josna Pankhania’s whistleblowing work on the Bihar School and the findings of the Australian Royal Commission of Inquiry (Pankhania, 2017). Of particular note for me was the essentialist East-West dichotomy which at times appear in the analysis. For example, one concern around trans-cultural dislocation of the guru-śiṣya (teacher-student) relationship is that Western communities import the teachings but not the controls, such that guru models are imported into spheres where the traditional role of a guru is not understood. Pankhania does note that this rhetoric is problematic. The Australian broadcaster ABC suggested that yoga taught according to Western standards would result in a decrease in abuse by asking, ‘Is the claiming of yoga now by the West as a western practice going to save it from abuse?’ Pankhania noted that ‘This concept is not only problematic, but also symptomatic of the West’s continued angst about ‘the white man’s burden’, the supposed duty of the white race to engage in civilising missions to liberate the ‘savages’’ (Pankhania, 2017: 115). Pankhania links this issue with the much broader debates around identity politics and the postcolonial critique, by noting that, ‘As ‘the white man’s burden’ is unable to convincingly justify European colonialism, so too a crisis of ethics in any yoga organisation can surely not be adequately resolved through the process of cultural appropriation by the West. Concern with abusive gurus is certainly very much present in Indian society, too.’

Women-oriented Iyengar Yoga

Agi Wittich, PhD candidate in the Department of Comparative Religions at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem joined us in this session to share her findings to date. Agi is working on ‘Yoga for Women in the Iyengar Yoga Tradition’. One of Agi’s supervisors is Yohanan Grinshpon, who’s Silence Unheard: Deathly Otherness in Pātañjala-Yoga (2002) has been a longstanding favourite of mine (for its classification of those who have interacted with the Yogasūtra and its unrelenting insistence on taking the implications of the practice for the yogin to its grisly conclusion).

Agi is focusing on women-oriented Iyengar yoga practice and the emergence of a historical narrative to lend authenticity to this practice within the Iyengar tradition. She notes that the Iyengar yoga tradition identifies itself as a continuation of an ancient and classical yoga lineage and argues that it justifies the inclusion of women and the adaptation of the practice through an alternative reconstructed narration of yoga history, in which women continuously practiced yoga. The current academic consensus is that there is little evidence of female practitioners of Haṭhayoga, especially āsana practitioners (we saw in Daniela’s presentation that there were few female yogi rājas, adept at physical practices, partly due to the structural challenges facing women who wished to pursue this lifestyle). Rather, historically, yoga appears to have been an androcentric practice. Whilst there may be evidence that women did practice they were probably a minority and had little impact on the standard hegemonic histories of yoga.

In addition to this reconstructed historical narrative of women practicing yoga Agi described the repurposing of ‘classic’ (androcentric) practices, adapting them to women's physical, physiological, mental and socially perceived needs. In an androcentric approach women are the marked category. Alternative practices for menstruation and the segregation of menstruating practitioners can be considered an ‘othering’. The requirement for a public (or semi-public) announcement of menstruation and the offering of alternative practices may be experienced as empowering yet also negatively impacts progression through postures and teaching qualifications. Agi’s research questions the ways in which this offers an inspirational model for women or whether it (further) restricts the options available to women and entrenches segregation in yoga classes. Her analyses suggest that it creates a glass ceiling beyond which women cannot rise in the Iyengar echelons, but does not have to result in negatively perceived segregation.

Agi is focusing on women-oriented Iyengar yoga practice and the emergence of a historical narrative to lend authenticity to this practice within the Iyengar tradition. She notes that the Iyengar yoga tradition identifies itself as a continuation of an ancient and classical yoga lineage and argues that it justifies the inclusion of women and the adaptation of the practice through an alternative reconstructed narration of yoga history, in which women continuously practiced yoga. The current academic consensus is that there is little evidence of female practitioners of Haṭhayoga, especially āsana practitioners (we saw in Daniela’s presentation that there were few female yogi rājas, adept at physical practices, partly due to the structural challenges facing women who wished to pursue this lifestyle). Rather, historically, yoga appears to have been an androcentric practice. Whilst there may be evidence that women did practice they were probably a minority and had little impact on the standard hegemonic histories of yoga.

In addition to this reconstructed historical narrative of women practicing yoga Agi described the repurposing of ‘classic’ (androcentric) practices, adapting them to women's physical, physiological, mental and socially perceived needs. In an androcentric approach women are the marked category. Alternative practices for menstruation and the segregation of menstruating practitioners can be considered an ‘othering’. The requirement for a public (or semi-public) announcement of menstruation and the offering of alternative practices may be experienced as empowering yet also negatively impacts progression through postures and teaching qualifications. Agi’s research questions the ways in which this offers an inspirational model for women or whether it (further) restricts the options available to women and entrenches segregation in yoga classes. Her analyses suggest that it creates a glass ceiling beyond which women cannot rise in the Iyengar echelons, but does not have to result in negatively perceived segregation.

Yoga in Britain

Suzanne Newcombe led a session on ‘Yoga in Britain: Reinforcing or challenging traditional gender roles?’ Suzanne is Lecturer in Religious Studies at the Open University and Research Fellow at Inform, based at King's College London. She is also working on the ERC-funded project AyurYog ‘Medicine, Immortality and Moksha: Entangled Histories of Yoga, Ayurveda and Alchemy in South Asia.’ Her doctoral research at the University of Cambridge was on the popularisation of yoga and Āyurvedic medicine in Britain. From 2002-2016 her work at Inform specialized in new and minority religious movements in contemporary Britain, especially originating in or inspired by South Asian beliefs. Hence her insight was particularly informative on the previous week’s topic of power and abuse.

Suzanne offered a two-part presentation drawing on her research from manifold sources—interviews, government records, physical culture journals and correspondence archives. Suzanne’s focus was on the historical context of how yoga became popular in Britain during the twentieth century. She noted that whilst yoga recapitulated all the problems of British society it was also a space for change. In the context of widespread popularisation in the 1960s and 70s she argued that yoga’s popularity can be partially accounted for by the way it simultaneously supported women’s traditional identities of wife and mother, as well as a more independent identity promoted by second-wave feminism. Women typically attributed better physical health and emotional well-being to their practice of yoga and this was an important reason for their participation in classes.

Of the factors influencing the popularity of yoga for women Suzanne notes in her work that of ‘bored housewife syndrome’, where resentments of middle-class women for their duties of managing every aspect of housework and childcare was an important part of how aspirations conflicted with restricted social roles. This was an impetus for second-wave feminists to compare their positions less favourably to those of men. For a fascinating discussion please see our reading to accompany this session (Newcombe, 2007: 37-63). Second-wave feminists also challenged the medicalisation of women’s experience especially for example around childbirth which Suzanne argues is closely related to the interest in yoga. The discussion touched around Western and Āyurvedic medicine—my view of the hegemony of Western medicine was tempered by Suzanne’s incisive suggestion that the unquestioned supremacy of Western allopathic medicine was (only) between the discovery of Penicillin and the catastrophe of Thalidomide.

Suzanne’s research has also explored the instructions given to BKS Iyengar when he received a monopoly to accredit teachers at adult education centres by the Inner London Education Authority. The ILEA insisted that ‘Instructional classes in Hatha Yoga need not and should not involve treatment of the philosophy of Yoga’. Thus the stipulation that ‘yoga could be approved ‘provided that instruction is confined to “asanas” and “pranayamas” (postures and breathing disciplines) and does not extend to the philosophy of Yoga as a whole’ came from the ILEA and not Iyengar’ (Newcombe, 2006: 42). Whilst Iyengar was already focusing on the physical practices of yoga rather than meditative ones this may have pushed him further in this direction. To my mind this is a significant factor in the development of modern globalised yoga as synonymous with āsana.

Suzanne offered a two-part presentation drawing on her research from manifold sources—interviews, government records, physical culture journals and correspondence archives. Suzanne’s focus was on the historical context of how yoga became popular in Britain during the twentieth century. She noted that whilst yoga recapitulated all the problems of British society it was also a space for change. In the context of widespread popularisation in the 1960s and 70s she argued that yoga’s popularity can be partially accounted for by the way it simultaneously supported women’s traditional identities of wife and mother, as well as a more independent identity promoted by second-wave feminism. Women typically attributed better physical health and emotional well-being to their practice of yoga and this was an important reason for their participation in classes.

|

| Figure 4: Lyn Marshall, Richard Hittleman and Alan Babbington on stage at the Royal Albert Hall on 8 July 1972. As found in Yoga & Health, October 1972, Vol. 2 (8): 3. |

Of the factors influencing the popularity of yoga for women Suzanne notes in her work that of ‘bored housewife syndrome’, where resentments of middle-class women for their duties of managing every aspect of housework and childcare was an important part of how aspirations conflicted with restricted social roles. This was an impetus for second-wave feminists to compare their positions less favourably to those of men. For a fascinating discussion please see our reading to accompany this session (Newcombe, 2007: 37-63). Second-wave feminists also challenged the medicalisation of women’s experience especially for example around childbirth which Suzanne argues is closely related to the interest in yoga. The discussion touched around Western and Āyurvedic medicine—my view of the hegemony of Western medicine was tempered by Suzanne’s incisive suggestion that the unquestioned supremacy of Western allopathic medicine was (only) between the discovery of Penicillin and the catastrophe of Thalidomide.

Suzanne’s research has also explored the instructions given to BKS Iyengar when he received a monopoly to accredit teachers at adult education centres by the Inner London Education Authority. The ILEA insisted that ‘Instructional classes in Hatha Yoga need not and should not involve treatment of the philosophy of Yoga’. Thus the stipulation that ‘yoga could be approved ‘provided that instruction is confined to “asanas” and “pranayamas” (postures and breathing disciplines) and does not extend to the philosophy of Yoga as a whole’ came from the ILEA and not Iyengar’ (Newcombe, 2006: 42). Whilst Iyengar was already focusing on the physical practices of yoga rather than meditative ones this may have pushed him further in this direction. To my mind this is a significant factor in the development of modern globalised yoga as synonymous with āsana.

The second part of Suzanne’s session presented careful evidence to nuance the picture of contemporary yoga as defined by neoliberalism and cultural appropriation. As part of her research Suzanne had participated in a teacher training offered by Baba Ramdev. She argued that it is in these contexts that Indian bodies can be found, including Muslim bodies, rather than mainstream yoga studios. She noted the light-heartedness of the attendees, regardless of religious affiliation, which softened the apparent contradiction between the diversity of attendees and a leadership which supports the supremacy of Hindus at the expense of Muslims. I am looking forward to more of this analysis in Suzanne’s new monograph which, according to its jacket, ‘resists the flattening of the neoliberal and cultural appropriation critiques’ (Newcombe, 2019).

The Fierce Goddess

Sandra Sattler was our final speaker and is conducting doctoral research on the iconography of fierce goddesses in Hinduism at SOAS. She is tracing the development of fierce deities such as Cāmuṇḍā and Kālī by analysing selected Purāṇas and art historical material. Her working title is ‘Cāmuṇḍā’s Glory: Representations of the Fierce Goddess in Purāṇic Literature and Indian (Temple) Art’. Sandra’s background completing her BA and MA at Goettingen University, also on fierce goddesses, and her work there as a research assistant for four years teaching Sanskrit, Sanskrit literature, goddesses, and Indian art gives her a strong background for her research project. I was keen to see how Sandra worked both as a textual historian and how she drew on art historical sources. In her research she is leaving aside questions of interpretation from a psychoanalytical perspective but will incorporate symbolic references contained in the primary sources.

The first part of her session entitled ‘With hollow eyes and skull garlands: Fierce goddess imagery in purāṇic literature’ gave an overview of fierce goddesses in Hinduism and her research to date. We turned to a close reading of key passages of purāṇic lore from the Agnipurāṇa. Here, Cāmuṇḍā, who appears as an individual goddess and as part of sets of divinities such as the mātṝkās and yoginīs, is invoked to defeat enemies and called upon with a variety of detailed epithets.

Strictly, goddess studies is not yoga studies, yet there is a close relationship between goddesses, yoginīs, and the powers attributed to those who are successful in yoga. The difficulty of disambiguation is similar to that of āsana (postures) and tapas (austerities). The divinizing of the feminine as the goddess opens a window on the manifestations of gender in the religious imagination and practice. The vidyā or incantation to the goddess whilst ostensibly directed at winning wars can also be used to distinguish the gross from the subtle body.

The readings for this session were a chapter from the Agnipurāṇa (Mitra, 1870: Ch. 135) and the introduction to Wild Goddesses in India and Nepal (especially 19-25). In this latter work I was intrigued by the tabulation of a typology of goddesses into mild and wild, or saumya and ugra—despite the author’s warning against dichotomous models. The tabulation was meant to be read as polyvalent, ambiguous and dynamic rather than dichotomous and static. Sandra was sensitive to the problematic Orientalist bias of much research in this area.

It was a privilege for me to curate the first such research group for the Centre of Yoga Studies and I am very grateful to the researchers who generously shared their findings. The wide-ranging presentations and discussions drew out points of content, method and theory whilst bringing in the research interests of all participants. We will be offering further study groups in due course. Please stay in touch with the SOAS Centre of Yoga Studies for forthcoming programmes.

The first part of her session entitled ‘With hollow eyes and skull garlands: Fierce goddess imagery in purāṇic literature’ gave an overview of fierce goddesses in Hinduism and her research to date. We turned to a close reading of key passages of purāṇic lore from the Agnipurāṇa. Here, Cāmuṇḍā, who appears as an individual goddess and as part of sets of divinities such as the mātṝkās and yoginīs, is invoked to defeat enemies and called upon with a variety of detailed epithets.

Strictly, goddess studies is not yoga studies, yet there is a close relationship between goddesses, yoginīs, and the powers attributed to those who are successful in yoga. The difficulty of disambiguation is similar to that of āsana (postures) and tapas (austerities). The divinizing of the feminine as the goddess opens a window on the manifestations of gender in the religious imagination and practice. The vidyā or incantation to the goddess whilst ostensibly directed at winning wars can also be used to distinguish the gross from the subtle body.

The readings for this session were a chapter from the Agnipurāṇa (Mitra, 1870: Ch. 135) and the introduction to Wild Goddesses in India and Nepal (especially 19-25). In this latter work I was intrigued by the tabulation of a typology of goddesses into mild and wild, or saumya and ugra—despite the author’s warning against dichotomous models. The tabulation was meant to be read as polyvalent, ambiguous and dynamic rather than dichotomous and static. Sandra was sensitive to the problematic Orientalist bias of much research in this area.

It was a privilege for me to curate the first such research group for the Centre of Yoga Studies and I am very grateful to the researchers who generously shared their findings. The wide-ranging presentations and discussions drew out points of content, method and theory whilst bringing in the research interests of all participants. We will be offering further study groups in due course. Please stay in touch with the SOAS Centre of Yoga Studies for forthcoming programmes.

Bibliography

Bevilacqua, D. 2017a. “Are women entitled to become ascetics? An historical and ethnographic glimpse on female asceticism in Hindu religions”. Kervan—International Journal of Afro-Asiatic Studies, Vol. 21: 51-79.

Bevilacqua, D. 2017b. “Let the Sādhus Talk. Ascetic practitioners of yoga in northern India.” Presentation at the conference Yoga darśana, yoga sādhana: traditions, transmissions, transformations. Krakow, 2016. Retrieved from: https://www.academia.edu/25569049/Let_the_Sādhus_Talk._Ascetic_practitioners_of_yoga_ in_northern_India

Grinshpon, Y. 2002. Silence Unheard: Deathly Otherness in Pātañjala-Yoga. Albany: State University of New York Press. http://public.eblib.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=3407943

Khanna, M. 2016. “Yantra and cakra in tantric meditation.” In: Eifring, Halvor, ed. Asian traditions of meditation. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2016. xv, 254: 71-92.

Lucia, A. 2018. “Guru Sex: Charisma, Proxemic Desire, and the Haptic Logics of the Guru-Disciple Relationship.” Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Vol. 86: 953-988. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaarel/lfy025

Mitra, R. 1870. Agnipurāṇa: A Collection of Hindu Mythology and Traditions, Chapter 135. Calcutta: Asiatic Society of Bengal.

Michaels, A., Vogelsanger, C. and Wilke, A. (Eds.). 1996. “Introduction.” In: Wild Goddesses in India and Nepal, Studia Religiosa Helvetica, Vol. 2: 15-34. Bern: P. Lang.

Newcombe, S. 2019. Yoga in Britain: Stretching Spirituality and Educating Yogis. Sheffield: Equinox.

Newcombe, S. 2007. “Stretching for Health and Well- Being: Yoga and Women in Britain, 1960-1980.” Asian Medicine, Tradition and Modernity, Vol. 3(1): 37-63. Brill: Leiden. https://doi.org/10.1163/157342107x207209

Pankhania, J. 2017. “The Ethical and Leadership Challenges Posed by the Royal Commission’s Revelations of Sexual Abuse at a Satyananda Yoga Ashram in Australia.” Responsible Leadership and Ethical Decision-Making. Research in Ethical Issues in Organizations, Vol. 17: 105-123. Emerald Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1529-209620170000017012

White, D.G. 1998. “Transformations in the Art of Love: Kāmakalā Practices in Hindu Tantric and Kaula Traditions.” History of Religions, Vol. 38: 172-198.

About the Author

Ruth Westoby is a doctoral researcher in yoga and an Ashtanga practitioner. Alongside practice and research Ruth runs workshops and teaches on some of the principle teacher training programmes in the UK. Her thesis is on constructions of gender in Sanskrit texts on Haṭhayoga at SOAS under the supervision of James Mallinson. For more information please see www.enigmatic.yoga.

Follow the of Ruth Westoby on academia.edu

Download this article as a PDF

Citation:

Westoby, Ruth. 2019. “Yoga and Gender Study Group: SOAS Centre of Yoga Studies–Chair Notes.” The Luminescent, 2 August, 2019. Retrieved from: https://www.theluminescent.org/2019/08/yoga-and-gender-study-group.html

• ONE OFF DONATION •

FRIEND . PATRON . LOVER

♥ $1 / month

♥ $5 / month

♥ $10 / month

♥ $25 / month

♥ $50 / month

Follow the of Ruth Westoby on academia.edu

Download this article as a PDF